Der Name

What's your name?/My name is/I am

There are thirteen weeks in a semester. It takes ten weeks to remember my name. My German teacher, whom I see and speak to every week, made this known to me on the tenth week of the semester. Endlich kenne ich deinen Namen. Endlich. Finally. Finally, I know your name.

She’s a kind person and a great teacher. I, too, have a terrible memory when it comes to names and faces. She’s from Germany, and it’s quite difficult to say my name for someone not familiar with Mandarin. It’s the X from my romanized name, Xiu Wen, that throws people off. Should it be a “ss” or “sh” sound? It doesn’t matter, I say. It really doesn’t. Pronounce it however helps you remember it. Then it is forgotten. And again. Then, after it is forgotten for the ninth time, I think, just maybe, I’m allowed to be a little bothered by it.

Der Name. In German, every noun comes with a gendered article: masculine, feminine, or neutral. Der, die, das. There’s little rhyme or reason to it, and because of that, I find it difficult to remember them. I make meaning out of it, so I don’t forget. Der Name is a masculine noun. It’s one of the first words I successfully remember. The name as a noun sounds like it should belong to a man. Names as masculine ideology.

In Singapore, a Chinese surname can be traced all the way back to your cultural lineage from China. Your ancestry. Your dialect group: Hokkien, Teochew, Hakka, etc.? Our great-great-grandparents were Chinese immigrants. They formed clan associations, the huay kuan, when they first moved to Singapore.

More important than the given name is the surname, passed down from father to children. When people get to know each other, here it’s commonly asked, 你姓什么?What’s your surname? How do I know which group you’re from, how do I trace you back and locate you within your ancestry? What is your name from your father? A patriarchy enables the name. How can the name be anything but masculine?

Der Name. Nah-Meh. In German, every syllable is pronounced; Name has two syllables instead of one. The word that is whole in English splits into two in German. There are two characters in my given name, 休 and 雯. In pin yin, xiù wén. In romanized English, Xiu Wen. My sisters’ names are Xiu Yi and Xiu Qi. I always thought that I was an outlier. My name was in two symmetrical halves, three letters balanced on each side.

When I was younger, I screwed up filling in forms all the time, the ones where you sign up for online platforms. In Chinese, the surname comes first, before the given name; 张, then 休雯. 张休雯. Chong Xiu Wen. Back then, I didn’t know what a first or last name was. I filled up the fields in that order: first name, Chong; last name, Xiu Wen. The interface greets me: Hello, Chong! I didn’t understand why a computer was addressing my entire family.

I eventually got it right by changing the order: first name, Xiu Wen, last name, Chong. Xiu Wen Chong. The father moves behind the daughter. Then, interfaces would greet me with: Hello, Xiu! They’ve taken the liberty of shedding the second half of my given name. I was now lopsided, missing one half. All three daughters of my father have the romanized Xiu, but in Chinese, I am different; my Xiu is 休, and my sisters’ is 秀. In English, we are homogenized to the same three letters.

I don’t know how to convey this. Staring back at me is, “Hello Xiu!” and there’s no way I can even begin to explain myself. I am defeated by three letters and a greeting.

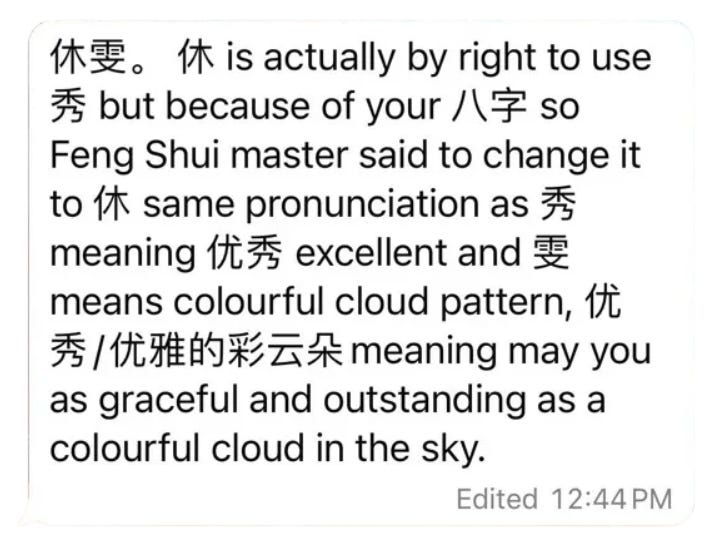

Dein Name. Your name. People like to ask, in cursory introductions: What’s the meaning behind your name? I look blankly at them in response. For the majority of my life, I’ve never known, I’ve never been told, and I’ve never asked. I’m bothered by these intricacies around my name, but I am only to blame; I’ve never known myself or my name, so how can I lay claim to it?

Isn’t it true that I’m worse than people who forget my name?

Last year, I finally asked my mother the question that I’ve wanted to know the answer to for so long but for some reason, never asked.

I was disappointed. I believed that after all this time, when I finally got to know my name semantically, there would be this great revelation, and then, a calm settling into the name I’ve lived with for years. I felt nothing. Like many others, my Chinese parents believe in 风水 fēng shuǐ, literally translated as wind and water. It is an ancient practice of following the flow of energy, 气. Some parents consult feng shui masters to name their newborn children.

The description of my name, “优秀/优雅的彩云朵; graceful and outstanding as a colourful cloud in the sky”, was so fanciful, so elaborate, that it felt almost artificial. Was this really what I meant? Feng shui, my parents’ beliefs, and their desire for me to be a good person, enabled the act of naming me, an act I know is love. But their beliefs are not mine, so I am estranged from my own name. Even after learning the meaning behind my name, I am muddled, I cannot find clarity in a name I’m still unable to claim.

Learning about my own name is a lot like learning a new language. For the longest time, I only knew the syntax of my own name, the building blocks of it, just like how I only know individual nouns, verbs, and grammar rules in German. I even understand my name; its true semantics. If someone spoke to me in simple German, I would be able to understand them, just like how I fundamentally know what my name means. But at the level of expression, the level at which I create my own meaning, is the part of language that I’m struggling the most to access.

So, past every intricacy, I’m making my own introduction.

Mein Name ist Xiu Wen. I’m 休雯. It’s pronounced ‘ss-ie-w’ in Xiu, and ‘wuh-en’ in Wen. The first word is pronounced in 第四声, meaning the fourth tone; it is a striking and downward xiù. The second word is pronounced in 第二声, meaning the second tone, wén is moving upwards and peaking at the end. It’s xiù wén. Still, you can pronounce it however you like because it can be quite tricky. 休 xiù is strange, it is typically pronounced as xiū, the character reminds me of 休息 xiū xi, meaning to rest. I love yoga and reading and things that make me relaxed. I like to see 雯 wén as made up of two characters, 雨 and 文. 雨 yŭ is the character for rain, which I like waking up to; it means I will most likely sleep in. 文 wén is my favourite because it reminds me of 文学 wén xué, my first love, literature. My name means rest, rain, and literature. My name is Xiu Wen.

What’s yours?

Hey, it’s Xiu Wen.

I’m been learning German for quite some time now, and stuff like this has been brewing in my mind for weeks now. I’m writing this all in one go, almost obsessively; I think you would understand.

My name is difficult, and I truly understand when people don’t immediately get it. Strangely, I’ve gotten quite used to it being forgotten. It’s the same situation where they point at me and attempt to muster up a garbled sound before I obligingly step in to give them what they’re looking for. The silver lining here is that I get called on less often in class, I can tell, because they’ve forgotten my name.

There is little sadness, more reflection. Names carry so much history, and the only real thing I feel sad about is that I’ve not come to know my name sooner. When I was younger, I was fully convinced that I would find an English name for myself. I thought I needed one. Now, I’m pretty sure I don’t want one, at least not for now. It’s pretty fun to watch people struggle to pronounce it.

Just kidding, of course. It’ll pose some real-life challenges, in work, maybe? Even my Dad got an English name. Sometimes people ask me what my English name would be, and the answer is always I don’t know. I don’t even feel at home in a name I’ve had for twenty years, let alone in a random English one. It sure won’t be an easy pick, perhaps, there won’t be a pick at all.

Love from,

Xiu Wen

This piece was beautiful and so is your name! Take so much pride in it and make sure everyone knows it! It has always bothered me how western/biblical names are the only ones people seem to remember or are able to pronounce. The human tongue is capable of saying far harder words than someone’s name, and we owe it to others to learn and say their names correctly. It makes me so sad when people with cultural names give themselves a nickname just so others have something “easier” to call them. No!!! Tell me your name and correct me until I get it down! Your name is too special and crucial to your identity not to.

Good to fill in the blanks of what you name signifies, better to have a known than an unknown, then even better to set the meaning aside and create your own meaning. People are judging us all the time based on what they think our past was.